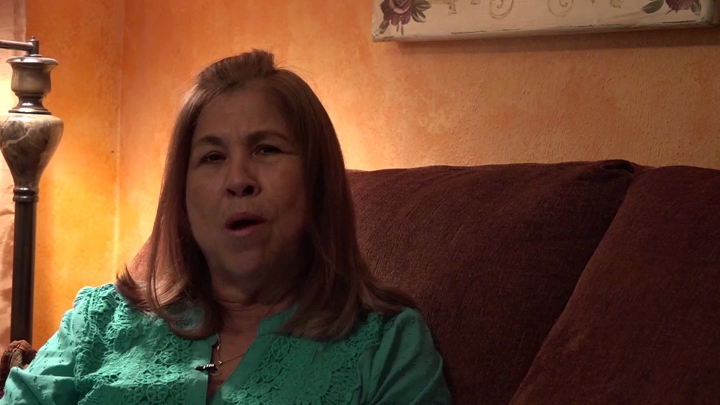

Payne / Neighborhood Types and Childhood Sports

sign up or sign in to add/edit transcript

Interviewer: So, you mentioned before when we were talking about your neighborhood—or I’m sorry, when we were talking about athletics, going to different places, and playing different teams, you said you knew what places not to be at late at night. Payne: Yes. Interviewer: Can you tell me maybe about which places were they and what were some of the things that your parents or the community warned you about? Payne: I think, you know—and I’ll say this, things have changed to some extent. Certainly, when we grew up, you didn’t go to Vidor after dark. That was known. You very seldom caught yourself late at night in Lumberton. Matter of fact, if you had to go to Orange, there were two ways you could go to Orange. You could go over the Orange bridge or you could go through Beaumont and then go through Vidor to get to Orange. No one would go through Beaumont through Vidor to get to Orange. You’d always go over the Orange Bridge. If you were going through Vidor, you would certainly gas up before you stopped so you wouldn’t have to get gas there. I don’t want to be too harsh on Vidor, because everyone in Vidor wasn’t that way. Unfortunately, there were a number of people—it was the home of the Ku Klux Klan. It was a place where they were very outspoken about their hatred towards people of color. I don’t think they hid that at all. Now that’s not to say everyone in Vidor was that way and certainly they were very outspoken, and we understood that. A good thing about high school sports, you generally play at your home one time and then they got to come to your home. So, you’d remember, you know. We’d come play you guys, and you don’t take care of—you try to mistreat us, that’s fine. You do have to come back to Port Arthur. We all understood that. One of the things that you’ll look at if you look at the research—they call it the Beehive which was the gym which is where we played basketball. It was one of the most feared places to play basketball, high school basketball in the state of Texas. It was because it was so small, and the stands were right on the court. The basketball team was here and the people in the stands were right behind them. It was the next bench. I wasn’t like you had some chairs and there was some area. No, it was right there and so it could be intimidating to a vesting school that when you walk into the Beehive. It’s loud. Everybody’s full of energy. We—not necessarily threatening people, but we certainly remember how we were treated when we went to your school and you can treat us, if you want, badly, but you do have to come back home. That was pretty much our attitude. Interviewer: So, we’ve heard from a number of people who grew up in this area that athletics, sports, basketball, football seem to be a way to really equalize things in some way. It was the beginning of desegregation to some extent, but also it was, like you said, that was where you could challenge people racially and show them things. Would you agree with that? How would you characterize that? Payne: Sports, basketball, football is in southeast Texas. It was the way of life. People used to plan their vacations around the state championship because my high school, especially in the eighties, we were known for being contenders in the state basketball finals every year. My year, we actually won, the 1986 team, but it was a dynasty as many people would argue. You may not like us, but you will respect us on the court because it was the one place where you could argue race mattered but you couldn’t stop us from being who we were. You know, even with basketball there were stereotypes. Well, the reason you guys are dunking and jumping out the gym is because you’re black and you’re great athletes and all that other stuff. When you play the white schools, you have to watch because they’re better shooters than you guys. It was interesting when we played sports, you could tell the coaches would coach defensively differently when they played us because they assumed we’re faster, we jump higher, and we can’t shoot. So, they would play a tight zone. Never play us man-to-man because we could outrun them. Which was the stupidest thing in the world but that’s what everybody thought. We were good at basketball, but we weren’t good because we were black. We were just good. We didn’t have—and I think a lot of it was socioeconomics—we did not have baseball to play. We didn’t have golf clubs. I didn’t play golf until I got to college. I didn’t even know we had a golf team to be honest. So, all we did during the summer was play basketball. We played basketball. We ran track. We played football. That’s what many of us could afford to do, many of us could afford to do, because basketball—ten people could play with one basketball. Twenty-two people could play with one football. Track didn’t require anything other than a boulevard where you could race each other. Baseball on the other hand, everyone had to have a glove. We didn’t have—everyone in our neighborhood didn’t have gloves. If you had one glove, that person always played first base and we played straight base. So, in the summers when people on the east side were playing baseball, and golf and tennis and all the other stuff, swimming, we just played basketball and we played football. Needless to say, when it came time for basketball season, we didn’t have to get our basketball legs ready. We’ve been playing basketball all season. I think a lot of that influenced our abilities. Now, I think where it really helped was that the competition that we learned on the basketball court, we tried to integrate that in the academic arena.