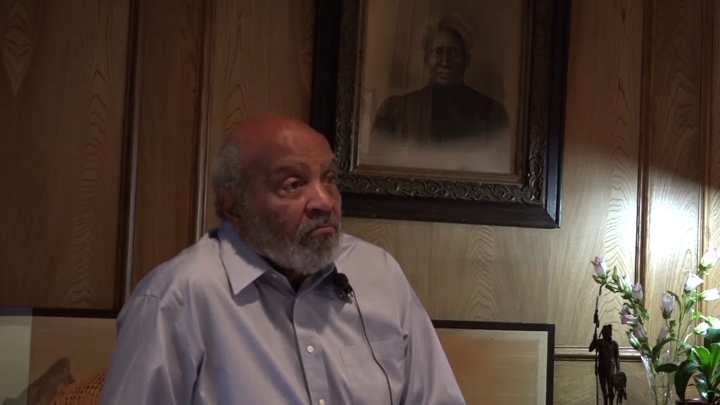

Aaron / Discrimination and Integration

sign up or sign in to add/edit transcript

Interviewer: You talked about Pleasantville and you had mainly an experience growing up with African-Americans versus being in the city of Houston because it was on the outskirts of Houston, Pleasantville. So— Aaron: Well, I don’t know if you can call it the outskirts. You know, Pleasantville wasn’t but two or three miles from Fifth Ward. A lot of the people—we had another black community on our side called Quinn Park. It was about five miles from downtown. I don’t know if you could call it on the outskirts of Houston. It was a small enclave though. Like I said, it was just something—a little spot of land that they decided to develop, decided to build some houses about three miles from Fifth Ward for black people. I think one of the—one guy that was involved in that who had something to do with developing those houses was Justin Robertson who later became a city councilman. In fact, he was a black city councilman in Houston, TX. He was involved in putting that development out there. That’s one reason they got the park in Pleasantville right now that’s named after him. Justin Robertson Park. Interviewer: Can you recall any first experiences with discrimination and if so, can you talk about that? Aaron: First experience? Yeah, I can recall experience with discrimination. As a kid, like I said, we used to go to Louisiana. I don’t know if you call it discrimination, but I could sense that blacks and whites wasn’t getting along too well. My grandfather—in the country, integration started in the country before it did in the city because blacks had land. Right across the street from us was a white man. Right directly across the street and that’s before the city was integrated and my grandfather would tell us, “Y’all don’t go on that man’s property.” Which means we never did. He would never speak to us and we would never even speak to him. So, I could tell cleavage between black and white back then as a kid growing up. (inaudible) in Houston. I ain’t had no real—outside of I believe, friends going downtown and they had a (inaudible), was still segregated. Blacks had to eat over here. When I was a kid, I experienced that with my mother one day. Of course, black schools. Blacks went to black schools and whites when to white school. I remember when we first started integrating schools. Had a school in Fifth Ward named McReynolds. That was where blacks on this side of town—that was the first school that we started integrating. Yeah, I remember that. Segregation. Interviewer: What was that like to start integrating schools? Aaron: Start integrating schools? It was—we felt it was positive. I remember it causing division in the black community because all of us did not go to McReynolds. I was continuing to go to Phillis Wheatley, you know, the black schools (inaudible) and some of us that went to the white schools started to feel a little privileged, you know what I mean? So, it caused a division in the neighborhood. The ones going to the white schools, they’d associate with themselves and we’d associate with ourselves. It was like a competitive thing, you know, a division. I remember it did that.