Wilborn / Before and After Integration

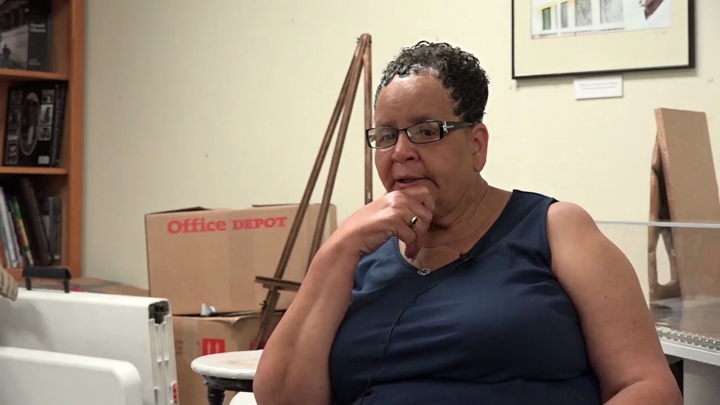

sign up or sign in to add/edit transcript

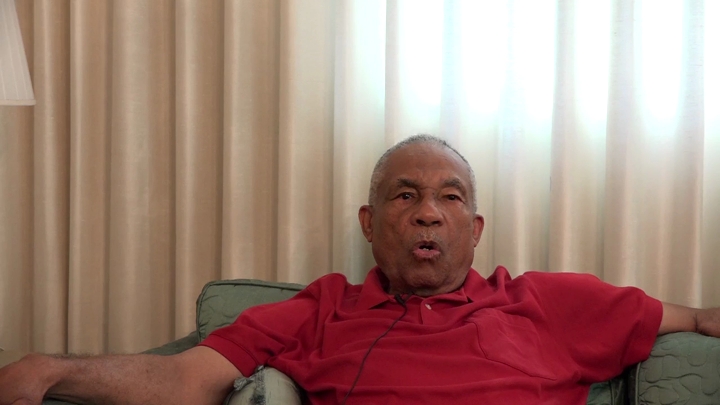

Interviewer: I wanted to ask you, did a lot of black teachers lose their jobs after integration? Wilborn: No, no, no. Nobody lost jobs. Interviewer: So many stayed in the Marshall system? Wilborn: Uh-huh, yeah. Interviewer: Did you hear of any other places, a lot of black teachers losing their jobs because of integration. Wilborn: I think that pretty well, in this area here—I’ve heard of people losing their jobs. East Texas, believe it or not, most of them were able to keep their jobs. Interviewer: What about teaching materials when you were a teacher both times, before integration and after? Wilborn: Well, I had a very bright principal. He was supposed to be a concert musician, but anyway, we had plenty of material. I’m going to be frank with you. I, as a teacher, always liked to use material that the students made rather than bought material. I never did use my budget, even when we integrated. I told the principal you could have it. My students will make theirs. I know before we integrated, I was teaching science and my students did an incubator, egg and all, but they did it crudely because I’m not artistic in making things. My opponent, the other teacher, same grade, she is an artist because she taught me really how to draw a little bit, so. It was well done. Laid out there. Mine was crudely done, I must say, but students did it. I direct and all. Matter of fact, they read encyclopedias and all. Incubators and what it consist of. About the egg, you know. Had the flashlight bulb and everything in there. So, we made this, and they wrote a report about it. We won first prize. Oh, she was hot. I know why I won, I did it—I mean, the students did it. I just—what little I did, what I know about carpentry and all that stuff. Anyway, it was done. That was before we integrated Dunbar. I think I was about to say—I know where I left off now about that math deal. We were—they sent me to Price—at Crockett we were outscoring everybody out there and the sent us to—I was a math teacher over there. That was the Texas basic skills. They gave math for fifth grade math students. Went to Price T. over there which was a predominant—I told my principal—oh yeah, about memorizing. I told my principal one thing we can do is memorize. I said, I don’t understand why they not scoring better than that at Price T. during that time, you know, they were down and so forth. Had no idea I was going to end up there. I knew one thing when they changed the format of the school to K through fourth, then had the fifth and sixth grade school, I ended up going to—I didn’t end up going to Sam Houston, predominantly white. I went to Price T., predominantly black. I said oh, my big mouth got me. So, that’s pressure on me. I took it to be anyway, but the first year, we outscored the predominantly white school, Sam Houston, and each year it got worse. First year, we scored ten out of twelve. Only, two points from being eleven out of twelve and six points from being twelve out of twelve. The second year we took it, we were eleven out of twelve. Only about five points from being twelve out of twelve, so I asked the principal, I said, “Give me the slow students. These smart students going to score anyway. We want to do twelve out of twelve, they’ll pan out. They’ve done all they can do. I got to pull the slow students up.” So, he consented. I said, “You want twelve out of twelve you’re never going to get it.” So, he gave in and gave me one class of slow students. That year we got twelve out of twelve. Interviewer: Wow. What year was that? Wilborn: I can’t tell you, but that’s the year I got promoted. So, predominantly black school outscoring predominantly white school, so they got to get rid of me. I didn’t get the principals jobs earlier because of my attitude in answering the questions and so forth because they didn’t like the answers I was giving. This time, I didn’t even have an interview. Do you want the job? Would you rather be a career—during this time, they started giving you extra money, two hundred dollars a year, for being a career teacher. Do you want the two hundred dollars—was it two hundred—two thousand dollars is what it was. Think it was two thousand dollars a year. Do you want that, or do you want to be a principal? I said I went to school to be a principal. All my life, I wanted to be one so yeah, I’m going to take that job there. I can be knocked down from this. I can be knocked down from the other one, but the chances are slim. So, that’s how I became a principal, because— Interviewer: What year was that? Wilborn: (inaudible) but I don’t recall. I know I stayed over there about, let’s see, about let’s say seven years (inaudible) must have been about 1985.

| Interview | Interview with John Wilborn |

| Subjects | Work › Occupations |

| Race Relations › Black-White Race Relations | |

| Discrimination or Segregation › Discrimination or Segregation at School | |

| Education › All-Black Education | |

| Education › Elementary Education | |

| Education › Education and Integration | |

| Education › Teachers and Administrators | |

| Historic Periods › 1980s | |

| Tags | David Crockett Elementary School, Marshall, TX |

| Sam Houston Middle School, Marshall, TX | |

| Price T. Young Middle School, Marshall, TX | |

| sign up or sign in to add/edit tags | |

| Interview date | 2015-06-23 |

| Interview source | CRBB Summer 2015 |

| Interviewees | Wilborn, John |

| Duration | 00:06:23 |

| Citation | "Before and After Integration ," from John Wilborn oral history interview with , June 23, 2015, Marshall, TX , Civil Rights in Black and Brown Interview Database, https://crbb.tcu.edu/clips/1453/before-and-after-integration, accessed March 05, 2026 |